August 26, 2010 – Christine Musil, Director of Marketing, Informative Graphics Corporation

The issue of production format in eDiscovery has long been discussed, argued and downright misunderstood. Historically, attorneys produced documents in paper form or electronically in TIFF or Adobe® PDF format. Even documents that originated electronically were often either printed and re-scanned or batch-converted to TIFF or PDF. The December 1, 2006 amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) – specifically rule 34(b) – made the default obligation to produce a document “in a form or forms in which it is ordinarily maintained or in a form or forms that are reasonably usable” unless the requesting party – or failing that, the producing party – specifies a different format.[1. Committee on the Judiciary. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. 111th Cong., 1st sess., 2009.] Does this demand that the producing party must deliver all documents in their original, native format (e.g., Microsoft Word or Excel)?

The knee-jerk reaction of some has been to demand native production without really understanding why the native format is or is not necessary for that case, and without knowing whether or not they have the software necessary to actually access all of the data they are demanding.

“Too often one or both sides do not understand the software technology involved.”

For example, in Armor Screen Corporation v. Storm Catcher, Inc., 2008 WL 5262707 (S.D.Fla. Dec. 17, 2008), defendants requested native file production, but were then unable to read files with a .SAV extension. The defendants demanded the plaintiffs then produce hard-copy printouts of the SAV files. Magistrate Judge Ann E. Vitunac refused to compel the plaintiff to grant the defendant’s request because SAV files, openable by a number of “statistical computer packages,” would in fact qualify as a “reasonably accessible format.” Too often one or both sides do not understand the software technology involved. This makes agreeing on a production format difficult and frustrating and often requires the court to make the ultimate determination.

Native, Not Native or Both

As long as both parties agree at the onset, TIFF, PDF, native or a combination of those formats may all be acceptable unless the parties fail to specify a format. According to Principle 12 of The Sedona Principles:[2. A Project of The Sedona Conference Working Group on Electronic Document Retention & Production (WG1). The Sedona Principles: Second Edition, Best Practices Recommendations & Principles for Addressing Electronic Document Production. June 2007.]

Absent party agreement or court order specifying the form or forms of production, production should be made in the form or forms in which the information is ordinarily maintained or in a reasonably usable form, taking into account the need to produce reasonably accessible metadata that will enable the receiving party to have the same ability to access, search, and display the information as the producing party where appropriate or necessary in light of the nature of the information and the needs of the case.

What Does “Native” Really Mean?

According to eDiscovery expert George Socha of Socha Consulting and the Socha-Gelbmann Electronic Discovery survey, confusion abounds about what native actually means. He notes that there are actually four categories of electronic discovery formats in terms of production, review and processing – true native, near native, near paper and actual paper.

True native files are copies of the original documents in the format created by the authoring application, like DOC or XLS. Metadata should be intact, if preserved properly. This is what most parties have in mind when asking for native production.

Near native formats can include many different types of files, depending on the perspective you take. Attorney and eDiscovery expert Tom O’Connor defines near native as various ways to render native files so the content and metadata are electronically accessible. Socha adds that relational databases and email sometimes fall in the near native category. Some experts would include electronically converted, searchable PDFs in this category, like a Word document that has been converted and retains the searchability and some metadata of the original file (metadata is discussed in more detail in the next section). Socha disagrees, including these instead in the next category, near paper.

Near paper are TIFF or PDF files that cannot be searched or indexed, and sometimes those that can. Lack of searchability has increasingly made TIFF production objectionable and is perhaps the most cited reason for requestors arguing that TIFF does not comply with FRCP rule 34(b). These formats can be rendered text-searchable by undergoing Optical Character Recognition (OCR), but OCR can yield imperfect results in terms of search accuracy and the results are generally inferior to electronically originated documents converted to PDF with text intact. Also, the text must be sent separately, usually as a TXT file, requiring that both the TXT file and TIFF image be reviewed and redacted separately. (See Electronic Redaction later in this document.)

Paper includes documents that originated in paper form or digital files that have been printed to paper. Clearly paper offers no searchability or other time-saving electronic review methods.

O’Connor takes a slightly different view, preferring a more inclusive category of “reasonably usable” that is used in the rules and under the Sedona comments noted above. It includes documents that are not in their native format, but are searchable and have the metadata intact so they are highly functional for discovery purposes. Socha has a different take on “reasonably usable,” seeing it as an attribute of one of the four forms of production summarized above rather than as a separate form. Says O’Connor, “the category ‘reasonably usable’ is the one used in the rules so I prefer that phrase, but I think that George and I are on the same page with regards to the handling of documents, he just drills down a little deeper with his definitions.”

Metadata Preservation/Production

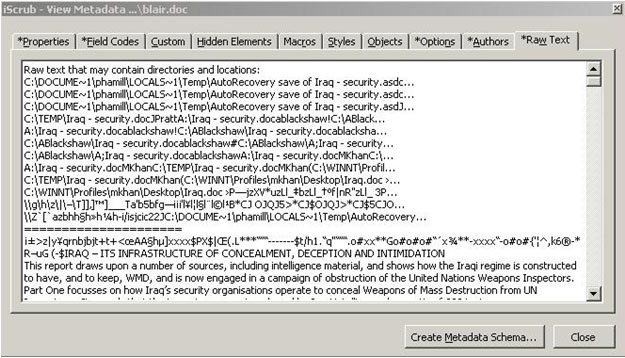

Preservation and production of metadata in a usable form is at the heart of many arguments against converting native documents to TIFF or PDF. O’Connor notes, “Metadata was originally a term used to refer to computer data such as date created/modified, author, etc. Now, the definition of metadata has expanded to include hidden material that does not appear when a document is printed out. Examples of this would include hidden rows, cells and formulas in Excel, and Track Changes and comments and markups in Word.” Just to show that this, too, is an unsettled area, according to Socha metadata was originally defined as “data about data,” a definition he says continues to apply today. (For those who want to dig deeper into the breadth and depth of metadata, Socha suggests searching on “metadata” as well as terms such as “Dublin Core.”)

Converting documents to PDF (even text-searchable ones) or TIFF may alter or fail to include the original creation date for the document or strip out all or most unseen content, again causing some requestors to demand native production with metadata intact. However, the created and modified dates are not always relevant, so this does not necessarily preclude TIFF or PDF being used as the production format. The unseen data, such as text revisions or comments, are also not brought through to the new TIFF or PDF file. Since these hidden elements may contain privileged information, this could be helpful to the producing party. It should be noted, however, that the mere suspicion of privileged content is not a sufficient basis for a blanket withholding of metadata. Spreadsheets are a notable exception, where eliminating formulas and hiding cells may be committing spoliation because they are intrinsic to the integrity of the document.

“There is clear case law supporting the production of financial spreadsheets in their native format…”

There is clear case law supporting the production of financial spreadsheets in their native format and discussion of spreadsheets warrants particular consideration when determining production formats.

In Williams v. Sprint/United Management Co., Case (230 F.R.D. 640) (D. KAN. 2005), Magistrate Judge Waxse from the Kansas Federal District Court decided that the defendant, when specifically instructed to produce digital spreadsheets “in the manner in which they were kept in the ordinary course of business,” should be subject to sanctions if they had scrubbed metadata and locked certain spreadsheet cells prior to production. In this case, Judge Waxse ordered a reproduction of the documents at the defendant’s expense, but decided not to impose sanctions because the laws on metadata production at the time were still new and fairly ambiguous.[3. Nerino Petro and Bryan Sims, “Avoiding ethical pitfalls with electronic documents: Part 1 – metadata,” The State Bar of Wisconsin Inside Track. June 16 2010.]

Even if you aren’t sure if metadata will be relevant, you always should retain an untainted set of the files, and only process from copies. In his 2005 paper “Beyond Data about Data: The Litigator’s Guide to Metadata,” Craig Ball, trial lawyer and special master of ESI for numerous Federal and State courts, states, “Fail to preserve metadata at the earliest opportunity and you may never be able to replicate what was lost.”[4. Craig Ball. Beyond Data about Data: The Litigator’s Guide to Metadata. 2005.] Proper preservation is important because metadata includes more than the data within the file itself. System data, like a file’s name and location, size, creation, modification and usage are also important to assess tampering, for example.

It is important that both sides understand the potential impact of metadata, if any, on the case. Without sufficient evidence that metadata is relevant, the court may not grant requests for it to be produced. Take Dahl v. Bain Capital Partners, LLC, 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 52551 (D. Mass. Jun. 22, 2009), where the requestor sought all metadata associated with emails and Word documents produced by the producers. Bain Capital responded by producing just 12 fields of metadata, which the court supported stating that “many courts have expressed reservations about the utility of metadata” and ultimately finding that:

Rather than a sweeping request for metadata, [requestors] should tailor their requests to specific word documents, specific emails or specific sets of email, an arrangement that, according to their memorandum, suits [producers]. This more focused approach will, the court hopes, reduce the parties’ costs and work. Furthermore, it reflects the general uneasiness that courts hold over metadata’s contribution in assuring prudent and efficient litigation.

“The issue of metadata should be discussed up front…”

The issue of metadata should be discussed up front or the opposing side may have grounds to claim spoliation or request re-production. Look at Bray & Gillespie Mgmt. LLC v. Lexington Ins. Co., 2009 WL 546429 (M.D. Fla. Mar. 4, 2009). Lexington requested that Bray & Gillespie (B&G) produce data in native format, and B&G did not comply. While B&G converted their native files to TIFF and stored the files’ metadata separately, they gave Lexington only the TIFFs and held back the metadata. When it was discovered that the metadata had been preserved and that they had violated Lexington’s native format request, B&G was subject to sanctions and the courts ordered them to produce the metadata to Lexington anyway.

Importance of the Meet and Confer

Discussions about production format, metadata and redaction should occur at the meet and confer session. FRCP rule 26(f ), the “meet and confer” rule, requires parties to meet at an early stage in the litigation process to discuss what information they have and how they will share it. Unfortunately, according to O’Connor, the meet and confer process often gets short-changed or skipped entirely. This leaves the producing party exposed to potentially costly and unexpected demands for native formats later in the process, perhaps after already producing in PDF or TIFF.

In Covad Communications Co. v. Revonet, Inc., 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 104204 (D.D.C. Dec. 24, 2008), the court ordered the producer to re-produce data in electronic format after having produced it in hard copy, but it ordered the two parties to share the $4,000 cost of privilege review, concluding:

This whole controversy could have been eliminated had [requestor] asked for the data in native format in the first place or had [producer] asked [requestor] in what format it wanted the data before it presumed that it was not native. Two thousand dollars is not a bad price for the lesson that the courts have reached the limits of their patience with having to resolve electronic discovery controversies that are expensive, time consuming and so easily avoided by the lawyers’ conferring with each other on such a fundamental question as the format of their productions of electronically stored information.

In a perfect world, the meet and confer would be thorough, civil and productive, and parties would clearly understand what they were requesting or expected to produce, but this is not often the case.

Browning Marean, Senior Counsel at DLA Piper, notes that “At these meet and confer sessions, it is crucial to have knowledgeable technical people present who are familiar with the discovery data and who know about file formats, production and redaction. Without an IT representative who understands issues around all document types that may be discoverable, such as the feasibility of producing the entire volume of data, and the possible concerns around privacy and proprietary information contained in the documents, any decision made could be completely unrealistic.”

“Give them what they’re entitled to – no more, no less.” – Browning Marean

The meet and confer is not only important for determining production formats, but it is also an opportunity to be up front about what data will be held back for cause of privilege or privacy. Marean suggests that parties agree on what data the requestor is entitled to and be clear about how it will be made available. “If a large H.R. database contains social security numbers which clearly constitute privacy information, explain to the other side and tell them which tables you’ll make available to them and in what format, and explain what has been redacted or omitted and why. Give them what they’re entitled to – no more, no less.”

Even judges are pleading for parties to conduct the meet and confer, since the lack of it can cause an unfortunate domino effect that wastes a lot of time and money. In Aguilar v. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Div. of the U.S. Dept. of Homeland Sec., 2008 WL 5062700 (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 21, 2008), Magistrate Judge Frank Maas emphasized the importance of the meet and confer meeting, saying “This lawsuit demonstrates why it is so important that parties fully discuss their ESI early in the evolution of the case. Had that been done, the defendants might not have opposed the plaintiffs’ requests for certain metadata. Moreover, the parties might have been able to work out many, if not all, of their differences without court involvement or additional expense, thereby furthering the ‘just, speedy and inexpensive’ determination of this case.“

Electronic Redaction

Redaction, the removal of privileged or privacy data from documents, represents another problem that arises in producing native documents. The typical method of redaction has been to print the documents, use a black marker to mask the information, then photocopy the marked-up pages several times to ensure complete obscuration before re-scanning back into the system. As the volume of ESI has escalated, this method of redaction is cumbersome, expensive and even unrealistic given deadlines to produce.

Electronic redaction involves redacting documents using a computer application like Adobe® Acrobat® or Informative Graphics® Redact-It®. Such tools can save significant amounts of time by allowing users to search for privileged phrases or automatically find privacy information, and they generally create a new, redacted rendition of the original document in TIFF or PDF format. Clearly, the biggest advantage is for text-searchable formats like PDF.

“The very nature of redaction is alteration of the document.” – Craig Ball

But how do you perform electronic redaction when native format is required? Redaction, by its nature, changes the document and must be saved to a new version, regardless of format. According to Ball, “The very nature of redaction is alteration of the document. No mechanism that you could use maintains an identical hash.” (A hash value is a unique identifying number that defines each digital file and is often used for forensic purposes to validate a document’s authenticity.) You start with the original document, select areas for redaction, and output the final, redacted version to a new document with necessarily different metadata (e.g., time stamps and author) and a new hash. No matter which format you choose for the redacted document, the redacted version must be tracked and managed in addition to the unredacted original.

Spreadsheets pose unique challenges to redaction. Ball notes, “Native redaction may be best realized in spreadsheets because you have the ability to remove whole categories of fielded information by row or column. But because spreadsheet data often entails dependencies—values that change based on other values – redaction can have unforeseen consequences if implemented incautiously. Disclosure is essential, so lawyers understand they are dealing with an altered document. There are no commercial tools to redact spreadsheets in their native format at this time, so it’s typically done using the native applications. Spreadsheets require careful attention during the meet and confer.”

Socha cautions that with true native redaction, unless you’re careful and savvy, you’ll likely change things you don’t really realize you’re changing. He notes, “This can break things. If there are formulas in a spreadsheet, you can ruin the document. Key numbers can disappear or change as part of a chain reaction.” He continues, “There are a series of challenges that differ from application to application; the industry hasn’t yet determined how to address native redaction. I have yet to see a proprietary approach or a broadly accepted method. True native review can be done with XML versions of Word, but needs to be done by someone who knows how.”

Redacting to a near-native or near-paper format is still the most prevalent method. Converting native files to TIFF or PDF and redacting them is safe, convenient, inexpensive and allows you to use reliable tools that are proven. Should a particular document be called into question, you can always produce the original source file with metadata completely intact.

What is clear, however, is that the meet and confer is the best, and in fact the required, setting to discuss issues of production formats, redaction and metadata so they do not end up being decided by the court. Lawyers need to understand more about the inner workings of the technology or need to bring along IT personnel that can help them navigate successfully through the preliminary stages. Attorneys needs to take eDiscovery technology training seriously and educate themselves to protect their own interests and that of their clients. It is irresponsible, perhaps even malpractice, for them to think and do otherwise.\r\n

Summary

Electronic discovery often presents complex problems with only partial solutions. Parties need to understand that dictating the same format across the board may not suit their ultimate goals. Each data set is different, and what must be revealed and concealed is unique for each case. By gaining a greater understanding of file formats, electronic redaction tools and metadata, lawyers can do right by their clients and can avoid regrettable situations in the courtroom which can range from embarrassment to sanctions to permanent damage to reputation of the firm and the client. Don’t take these risks unnecessarily. Take the time and bring the IT talent to the table to have a quality meet and confer. After all, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

About the Author and For More Information

Christine Musil is Director of Marketing at Informative Graphics, a leading developer of commercial software products for secure content viewing, collaboration and redaction. Founded in 1990, Informative Graphics products are deployed by thousands of corporations worldwide.

For more information, please contact:

Informative Graphics Corp.

835 E. Cactus Rd

Scottsdale, AZ 85254

Phone: 800.398.7005 (intl +1.602.971.6061)

URL: www.infograph.com

Disclaimer

Unless otherwise noted, all opinions expressed in the EDRM White Paper Series materials are those of the authors, of course, and not of EDRM, EDRM participants, the author’s employers, or anyone else.